Seasonal science: cranberry harvesting and turkey genomics – pass the stuffing

On your Thanksgiving table, consider the cranberry. Especially if you are so lucky as to have freshly prepared cranberry dressing in all its tart and tangy goodness. When you consider what went into getting those garnet jeweled fruits to your table, this unassuming side dish is remarkable.

While on vacation over the summer we stopped in Long Beach, Washington – home to the Cranberry Museum. I dragged everyone away from the carousel rides and saltwater taffy to see a modest but entertaining two-room display on the history of cranberry growing and harvesting in the coastal Washington area, alongside some working cranberry bogs. The irony of Wisconsinites learning about cranberries in Washington is that Wisconsin is far and away the leading producer of the crop.

If you grow cranberries, have patience. The berries grow on vines that have finicky soil preferences. The vines are fairly delicate and two years’ worth of growth is present at each harvest, so collecting the fruits is a careful process. The berries themselves are prone to cracking, which renders them ruined. And the harvesting? Collecting berries by hand is mind-numbingly slow and tedious, but mechanical harvesting must accommodate the fragile nature of the plant. In Wisconsin, growers typically wet-harvest the crop. Imagine the cranberry bog recessed into the ground, and with sides forming a wading pool. The bogs are flooded with water and bizarre harvesting machinery (such as a water-friendly tractor with a paddle wheel) is used to gently beat the vines. This releases the berries, which then float to the top due to their internal air chamber – like small antioxidant-packed balloons. The berries are collected on the water surface, resulting in the amazing aerial view you see in the top photo (courtesy of the Wisconsin State Cranberry Growers Association).

And now on to the main dish – the turkey that likely graces your table. Recently, poultry researchers (yes, there are scientists who focus on poultry, just as there are plant breeders, growers, and pathologists who focus on cranberries) announced a collaborative effort to sequence the turkey genome. Apparently researchers in the field take advantage of the seasonal focus on turkeys by making such announcements the week before Thanksgiving, hoping for some media pick-up; similarly, the completion of a genetic map of the domestic turkey was announced in November 2004. The media pitch appears to be working reasonably well, as they’ve gotten some good coverage.

The new genome sequencing data will allow researchers to do genomic comparison studies between domestic turkey and domestic chicken, whose genome is already available. The turkey sequence will only be a “draft sequence”, though, meaning that the quality will need to be improved in the future, and researchers are already giving warning that they will be approaching industry and federal sources for funding in 2009.

So what will knowing the full sequence of the turkey genome get you? Well, once it’s completed, look for studies analyzing genes that control muscle development, the genes that control the genes involved in muscle development, genes controlling fat formation, reproductive process genes, and likely a flock of additional papers on disease resistance genes. Domestic turkeys are not the heartiest in face of illness, as it turns out. However, at least according to one perspective, this is due to the extreme genetic homogeneity and relentless large-scale cultivation practices that the modern turkey industry relies on. Perhaps a little outbreeding is in order.

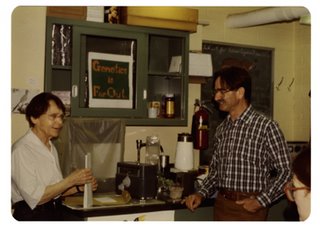

Interestingly, one of the scientists quoted in the turkey genome press release is Jerry Dodgson, a professor at Michigan State University. I took a class on eukaryotic molecular genetics from him when I was in grad school. He has worked on poultry for much of his career, mainly focusing on chickens and viruses causing chicken diseases, and is now leveraging his expertise and that of researchers in his laboratory to the domestic turkey.

Gobble, gobble indeed.

Labels: research, seasonal science